I. Establishment of the National Royal School of Drawing and Drawing Teacher Training

In the 1870s,the Terézváros district of Pest, which was aspiring to the status of a cosmopolitan city, was home to the most important institutions of the contemporary art scene. The intertwined history of the National Hungarian Fine Arts Society, the National Royal School of Drawing and Drawing Teacher Training, the painting and sculpture schools helped to create the building that today stands on the corner of Andrássy út and Izabella utca, and Kmety Gy u., Bajza u., Szondy u. Munkácsy Mihály u., the so-called Epreskert is home to the Hungarian University of Fine Arts, which offers university education in all fields of fine arts.

Several unsuccessful attempts to organise higher education in the Hungarian fine arts have been made since the mid-18th century. Probably because of dependence on Vienna and lack of funds, only a few short-lived private schools, large or small, have managed to go beyond the drawing up of plans. Those who chose to pursue a career as artists could train at foreign institutions, first in Vienna and then at the increasingly popular art academies of Munich and Paris. In the mid-19th century, the emergence of national sentiment deepened the desire for Hungarian art to become independent, and the growing links with foreign countries urged the adoption of European models of fine arts training.

In 1861 the National Society of Fine Arts was founded. After two years of wrangling, the statutes of the Society, approved in 1863, stated that the aim of the Society was "to help all branches of the domestic fine arts to perfection, to ennoble the taste for art and to spread the love of art." The Society did not have an independent financial basis and could only achieve its goals with the support of its patron members. Its wealthy patrons included, in addition to the monarch and members of the royal family, aristocrats, prelates and, later, an increasing number of wealthy bourgeoisie. Their extensive connections are illustrated by the fact that they even included the Queen of Belgium among their patrons.

The first of the Society's aims was to set up an art school. A committee was formed to plan the establishment of the future art academy. The members of the committee were : Soma Orlay-Petrich, Mór Than, Károly Telepy, Ferenc Plachy and Pál Harsányi. Their plans for the establishment of the academy were not realised due to lack of funding, but it was thanks to their initiative that one of the new members of the committee, Gusztáv Kelety, was commissioned by József Eötvös, Minister of Culture, to travel to Europe to study the work of academies of fine and applied arts.

Gusztáv Kelety summarised his experiences in his book "Art Education Abroad and its Tasks in Hungary". Kelety - with a rather strong sense of reality - did not consider the establishment of a full academic education feasible under the Hungarian conditions of the time. His proposal was for an institution providing basic teacher training, which he called a teacher training college, bypassing the word 'academy'. His concept was that young people preparing for a career as artists would be able to broaden their knowledge in well-equipped studios under the guidance of excellent masters. At the urging of the National Society of Fine Arts, Tivadar Pauler finally founded the predecessor of the Hungarian University of Fine Arts, the National Royal School of Fine Arts and Drawing Teacher Training School, on 6 May 1871, by ministerial decree, on the basis of a law sanctioned by King Franz Joseph I. The new institution started its operations in October 1871 at 6 Rombach utca, Terézváros, in a rented apartment in a private tenement house. Its aim, according to the plans of Gustáv Keleti, was to train teachers of drawing and to provide basic training for young people who wanted to pursue a career in the fine arts.

II. Home for the "artist's house"

The teaching staff included Gusztáv Kelety, then 37, "academic painter", director, Bertalan Székely, "historical painter", who taught figure drawing and painting; Miklós Izsó, "academic sculptor", who taught pattern-making; Frigyes Schulek, "academic architect", who taught architecture and ornamentation. In addition to these subjects, anatomy, military site drawing, descriptive geometry, perspective, woodcutting, applied art drawing and ornamental drawing were taught. Great importance was laid on the drawing from sheet and plaster casts. The drawing of the living model, which seems so natural today, was only included in the curriculum towards the end of their studies. Art history, psychology and education were taught at the niversity in Pest.

The modestly sized institution had 53 students. The free evening course for craftsmen engaged in a branch of the 'art industry' (in operation until 1885) was attended by 24 students in its first year. Occasional training courses were organised for practising drawing teachers. The initial training period was three years. Candidate teachers were entitled to a state scholarship in exchange for three years' teaching in the designated school after qualification. As the number of teachers increased, the institution had to rent more and more flats, with an annual rent of 11.000 forints after five years. Moreover, the expensive rented apartments did not meet the requirements of artistic education. The heavy sculpture could not be moved upstairs, and the rooms with damp walls did not have enough natural light. So after five years of operation, the school of drawing had to look for a building that was affordable and suited to its training needs.

The favourable public conditions meant that the National Society of Fine Arts was unable to carry out its expanding activities, but above all, one of its main activities, its exhibition programme, for lack of suitable premises. They could only hope to bring about a radical change in the life of the Society if they were to acquire a well-equipped house designed for their own purposes, which would serve as a permanent centre for Hungarian art and would offer the public a worthy environment in which to encounter the works of national and foreign artists.

In the spring of 1872, the Board of the Society decided to take steps to raise the necessary building capital for the construction of the future 'artists' house', also known as the 'Art Hall', and to acquire the land. The Board therefore appealed to the City Council of Pest, requesting that, when the future avenue was planned, the right of first refusal for an 800-square-metre plot of land be transferred to the noble and public purpose they had in mind. The construction of the Avenue was the largest and one of the most successful undertakings of Pest's urban planning. The works were managed by the Metropolitan Council of Public Works, established in 1870 to plan and carry out the most important tasks of urban development.

III. From very beginning to the ceiling fresco

On 8 May 1872, the General Assembly of the capital granted the request of the National Society of Fine Arts, and after lengthy negotiations, in 1874 it sold plots 78, 80 and 151 on the south side of the future avenue, beyond the Oktogon, to the Society for a fair price of 55,000 forints.

As the plots purchased exceeded the needs of the Society, about half of them were transferred to the Study Fund at the same price, with the consent of the capital, so that the Royal National School of Art and Drawing could build its own building there. Construction of the two buildings began at almost the same time.

The Fine Arts Society launched an international competition, which attracted 45 entries. The jury, composed of members of the Board of Trustees and distinguished Viennese architects, awarded first prize to Adolf Láng. On the basis of his design, work began from public donation on 12 April 1875, and just over five months after the beginning, the roof was put on on 26 September under the direction of the architect Napoleon Kéler, a contractor. The Renaissance palace in stone, modelled on the Palazzo Bevilacqua in Verona (built by Michele Sanmicheli in 1530), proclaims on its elegant, restrained façade that it was built from public donations. The interior stucco decorations are by Napoleon Kéler and the paintings by Adolf Láng. The coloured windows were made by Zsigmond Róth, a member of the Society, and donated to the future Art Hall.

The palace's richly gilded, stuccoed, column-arched marble-tiled entrance hall leads into the small but elegantly designed staircase, whose ceiling lunettes and octagonal framed allegorical figures on the first floor ceiling were painted by Károly Lotz, a teacher in the painting department of the Mint Academy and a celebrated fresco painter of the time. From 1863 onwards, Károly Lotz was continuously commissioned to paint murals in private palaces and public buildings. In addition to the frescoes of the Vigadó, the Keleti Railway Station, the Great Hall of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, the two chapels of the Cathedral of Pécs, the Matthias Church and many other public buildings, his main works include the ceiling frescoes of the Opera House and the murals of the Terézváros Casino. The Kunsthalle's tranquil, oval-domed staircase opens up to the right, airy space, with a gilded stucco loggia above the inner courtyard leading to the exhibition halls. The first home of the Society of Fine Arts and one of the Society's exhibition venues until 1945, the Art Hall was completed by October 1877. It was opened to the public on 8 November by the Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph. This was also the date of the opening of the representative exhibition organised for the occasion.

IV. Art education in a new building

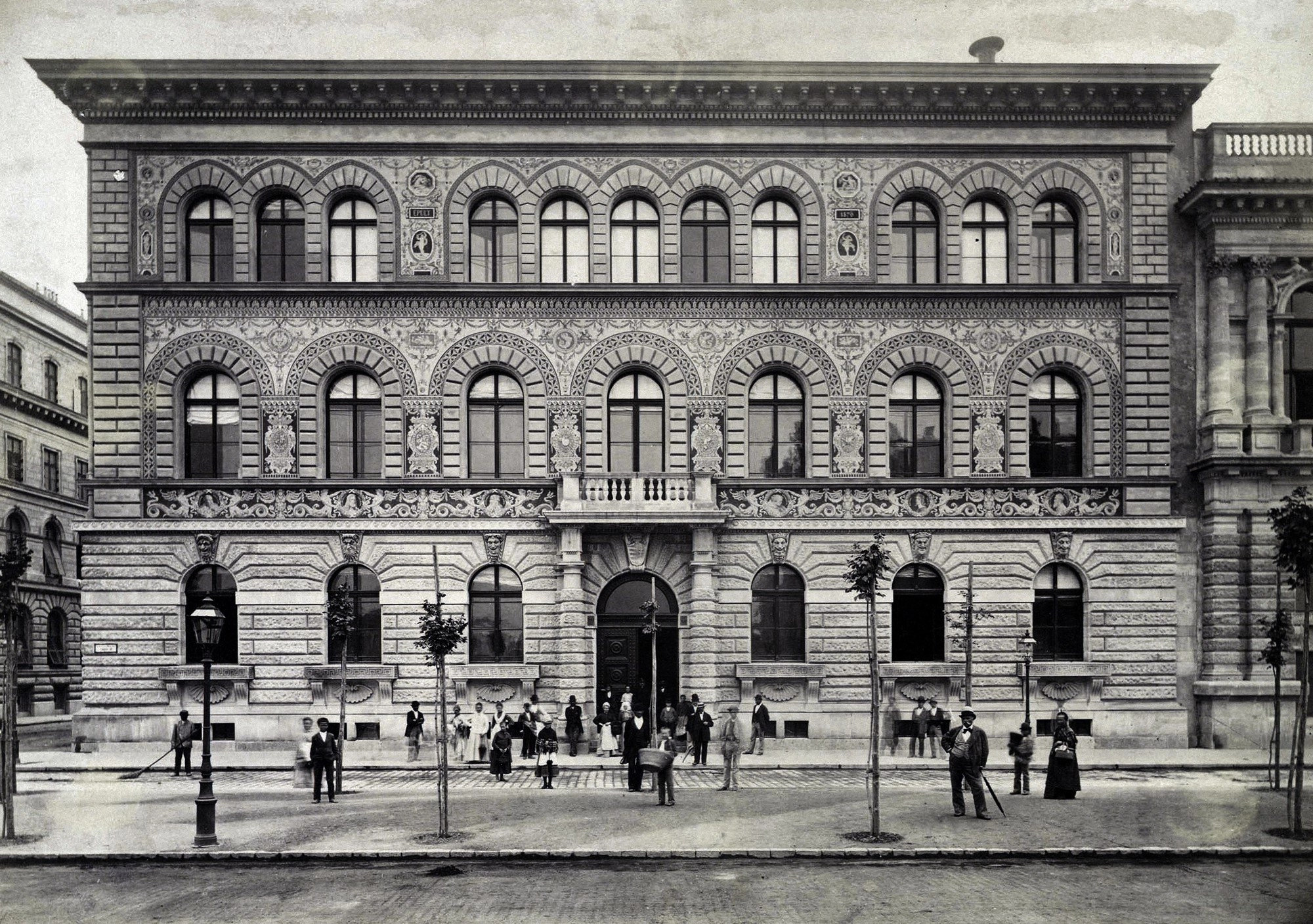

Lajos Rauscher, the institution's architect-teacher, drew up a plan for the construction of the new building on the plot of land purchased from the Fine Arts Society for the Art School at the corner of Izabella Street and Sugárút, on the instructions of Ágoston Trefort, the Minister of Education. Rauscher designed a simple but elegant building to meet the needs of the School of Drawing and Drawing Teachers Trainingl, as the Minister had requested. Construction proceeded rapidly and the new building was ready for the opening of the 1876/77 academic year.

The two-storey corner building was designed in a Renaissance style similar to the Art Hall. On the façade, the first floor cornice band and the semicircular window sills were decorated with sgraffito ornamentation in keeping with the style of the building. The medallions of the cornice strip show the portraits of Bramante, Leonardo da Vinci, Rafaelllo, Michelangelo, Dürer, Károly Markó and many other famous painters, sculptors and architects. The medallions are the work of Bertalan Székely, a teacher at the institute, while the other sgrafitto were designed by Lajos Rauscher.

Entering the building, you enter a small foyer. The entrance niches, with marbled walls, columns and colourful, gilded stucco mouldings, are decorated with statues of men of art-historical importance.

In the basement of the building were plaster casting workshops, and on the upper floors are still studios. The two buildings, built next to each other and with similar functions, were so popular with the general public of the capital that the empty plot of land next to them was purchased by the capital with the firm intention of erecting a building of similar appearance and function. The intention came true and the building is now the Old Academy of Music.

The building of the National School of Drawing and Drawing Teacher Training was extended towards Izabella Street in the academic year 1895/96. The building took its present form. After a few years of operation, the name of the School was changed to the National School of Design and Drawing. As a result of the drive for modernisation organisational and curricular reforms followed every year. From 1878, candidates for the posts of drawing teacher and had to take examinations in front of an independent board, the National Royal Hungarian Drawing Teacher Examination Board. The certificate awarded by the Commission gave the right to teach freehand drawing and drawing geometry. By 1893, four types of qualifications (secondary school, teacher training, civil school, industrial apprenticeship and drawing teacher) were awarded. In 1896, the year of the Hungarian millennium, as a consequence of the differentiation in education, the School of Applied Arts was spun off from the school under the direction of Kornél Fitter, and the duration of the training was increased to four years. The growing number of students meant that Károly Lotz's practical painting class was housed in the upstairs rooms of the Old Music Academy. Since the teaching of drawing was made compulsory in lower and secondary schools nationwide, in the hope of developing the artistic industry and public taste, the main activity of the School of Drawing was to train teachers of drawing. In the training of art students, the institution was limited to 'preparing' them for a career as an artist. In 1897, the training of trainee teachers of drawing was radically separated from the training of artists. We have to agree with the art writer Károly Lyka that the teaching staff, with their conservative tastes, 'were concerned about the intrusion of modern ideas and new stylistic trends into the studios' and wanted to protect the teacher trainees from these influences.

After completing their studies at the model drawing school, the trainee artists were able to broaden their knowledge at foreign academies or in the studios of famous masters. To create a higher level artistic education in Hungary, the so-called master schools were created by decree.

V. Epreskert

For the construction of the master schools, the capital allocated a plot of land of almost 4,000 square metres: the area bordered by the present-day Kmety Gy, Bajza, Szondy and Munkácsy Mihály streets.

The Master School of Painting No. I started its operation in 1882. Its director was Gyula Benczúr, one of the greatest masters of historical painting and a famous teacher at the Munich Academy. His famous portraits and historical works were created in the representative studio of the school. In 1897, Master School of Painting No. II began its activities under the direction of Károly Lotz, and the Master School of Sculpture under Alajos Stróbl. Gyula Benczúr's school specialised in panel painting, while Károly Lotz's specialised in fresco painting. Lajos Deák-Ébner was the head of the painting school for female students, which was located in the Várkertbazár.

When the site for the art schools was designated, the capital decided to build the artists' school in the so-called Epreskert, a secluded area of groves and bushes. The city, preparing for the millennium, encouraged the settlement of renowned artists by allocating cheap plots of land near the Liget and the Sugárút. Eminent artists of the Hungarian fine arts set out from here or created their works in the studio villas surrounding the Epreskert. The houses built by the artists blend in perfectly with the elegant palaces and villas of the area and are a good representation of the social status of art and artists at the time.

Adolf Huszár, György Zala, the architect of the Millennium Monument on Heroes' Square, Albert Schikedanz, the "architect painter", the architect of the Millennium Monument, and the designer of the new Art Hall, also on Heroes' Square, completed in 1896, worked here, to mention only the most famous. While in the former Lendvay Street a "sculptors' row" developed, in Bajza Street painters' studios were built. The villa of Árpád Feszty and Hungarian writer Mór Jókai were the focus of interest. Árpád Feszty married Jókai's foster daughter Róza in 1888. Widowed in 1886, Jókai moved to the artist colony with her foster daughter and her painter husband. Feszty worked in his huge studio on the ground floor of the large palace at 18 Bajza utca, while Jókai had rooms upstairs, including a fifty-square-metre study. The housere was teeming with social life.

The representative studios of Gyula Benczúr, Károly Lotz and Alajos Stróbl were located in the area of the Epreskert master schools. Their studio house, which blended in with the surroundings, was exclusively dedicated to education, since the most important element of the training of the artist candidates was to work together with the master and to participate in his work. The teachers of the master schools could spend most of their time in the Epreskert, without having to pay for the use of the studio. They all bought their own houses in nearby streets. Benczúr lived in Lendvay Street, Stróbl in Bajza Street. The teachers of the master school, but especially Alajos Stróbl, played a major role in the development of the Epreskert, creating the special atmosphere that still prevails today.

Stróbl's extraordinary talent and character were evident not only in his sculpture, but also in his way of life and the way he shaped his surroundings. In the mornings he would ride out of the Epreskert blowing his horn, organisedd huge costumed art parties and perform historical scenes with his students and guests. His studio had a fountain with goldfish, monkeys, peacocks, deer and stork walked around in his garden.

He filled the Epreskert with buildings and artefacts that were dear to him. He decorated his garden with copies of antique, medieval and Renaissance artefacts. But he also saved the beautiful Baroque Calvary by András Mayerhoffer, which was condemned to demolition when Calvary Square was redeveloped. Stróbl donated the first prize of 3,000 crowns he had won in a competition for the Baross statue to save the building. He and his followers demolished and rebuilt the Calvary in the Epreskert, which is now awaiting restoration. But he also placed a bronze replica of the statue of St George on horseback, cast in bronze in 1373 by Márton and Görgy Kolozsvári, which now stands in the Hungarian National Museum, and another replica at the entrance to the Epreskert.

During the renovation of the Church of the Assumption in Buda, he moved several of its original stones to the Epreskert, incorporating them into the designed surroundings. The strange and bizarre setting, which at the same time radiated tranquillity under the shade of huge trees, attracted art lovers. The garden was frequented by high and middle classes, Emperor Franz Joseph also visited the Epreskert on several occasions.

Bertalan Székely was appointed director of the Model School of Drawing, replacing Gusztáv Kelety, who died in 1902. As a result of the changing secondary school curriculum, the number of geometry lessons was reduced, but there was no change in the essence of education.

In 1905, Bertalan Székely left the institute and became the director of the Painting Master School No. II. Pál Szinyei-Merse became the head of the school. It was thanks to his work as director that teachers from the Nagybánya school, who had a more modern approach to art, were slowly brought into the institution. Károly Ferenczy started teaching in 1905, István Réti in 1913, Oszkár Glatz and Károly Lyka in 1914.

In 1906, Viktor Olgyai started teaching a new branch of art, the reproduction of graphic techniques. The work produced here has become one of the College's valuable collections, which contains 3,000 sheets of graphic art.

From the academic year 1906/1907, talented graduating teachers of drawing were given a scholarship to stay at the school for further training.

VI. The Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts

In 1908 the master schools and the school for women painters were administratively attached to the model school of drawing, and from that year the institution was called the Royal College of Fine Arts. In essence, however, teacher training and artist training remained separate. During the First World War, most of the students were sent to the front, and the building was converted into a military hospital. The canteen was used to feed the children of soldiers. Teaching took place in unheated rented rooms, in three-month courses, with the greatest financial difficulties. In some departments, work was suspended.

At the start of the academic year 1919/1920, the College was in complete disarray. The military hospital was replaced by army troops. In 1920 the government entrusted the reorganisation of the College to the art writer Károly Lyka. Lyka called István Réti, who had been teaching at the institution for several years, to help him with his work. The two men's plans came into force after the Ministry's approval.

First of all, the reform eliminated the fragmentation of institutions for the training of artists. It also merged structurally the art schools, the women's school of painting and the school of pattern drawing, which had been merged in 1908 on purely administrative grounds. A common approach was adopted to teacher and artist training. For two years after the compulsory entrance examination, practical and theoretical subjects were taught in the same way to teacher and artist candidates. Teacher candidates could only continue their studies after passing the second end-of-year examination with at least a good mark, and were awarded a teacher's diploma after two basic and two specialised examinations. A summer internship in a rural art school was made compulsory. With the exception of art history, the number of theoretical classes and studio practice was reduced in favour of the figurative studio. Hours in architecture, applied arts, visual siences and geometry were reduced, and ornamental drawing, movement composition, animal dissection and studio drawing were eliminated.

The management of the College has also been reorganised. From then on, the director was replaced by an elected Rector's Council, which was renewed every two years and whose elected president became the "rector magnificus". He was responsible for implementing the decisions of the Rector's Council and representing the institution. Under the rectorship of Károly Lyka, Oszkár Glatz, Gyula Rudnay, István Csók and János Vaszary became members of the teaching staff. In 1930, the period of study for secondary school teachers was increased from four to five years, in line with the training of secondary school teachers at other universities. The Rector's Council was allowed to add two years to the normal period of study for outstanding students. The teachers of the college were free to accept any so-called "postgraduate" students who applied to them.

The Second World War created a critical situation at the College. As a result, the 1944/1945 academic year did not start. Among the teachers who taught at the institution, which was reopened after the war, were Pál Pátzay, Aurél Bernáth, Jenő Barcsay, Róbert Berény, János Kmety, Endre Domanovszky, Géza Fónyi, Béni Ferenczy, Lajos Nándor Varga, Gyula Hincz, Károly Koffán. The new regulations of the College essentially developed the Lyka-Réti reform. It enshrined autonomy at the university level and made academic freedom complete. Twenty hours of figurative study and at least ten hours of theory were compulsory. The inclusion of optional subjects was also allowed. The subject of applied art was abolished, but students could study mural painting, mosaics, stained glass, tapestry design and construction. Conservator training began. With the dissolution of the National Fine Arts Society, the old Art Hall building, which had been used for teaching and exhibitions, was attached to the college. Today, it is still the headquarters of the College, connected to the original building of the College on the corner of Izabella Street and Andrassy Avenue. After the communist takeover of 1949, the educational reform brought the College under the jurisdiction of the Ministry. Sándor Bortnyik became the Director General. Teaching followed a precisely prescribed curriculum and programme. After two years of basic training, the three-year main technical courses were introduced. In the fifth year, students wrote a thesis, which was defended in a public graduation examination. After a successful defence, they were awarded an artist diploma. Teacher training was temporarily discontinued. The new secondary school curriculum removed art from the curriculum and primary school teachers were trained at the newly established teacher training colleges. Later on, there was a succession of amending and improving measures. The Department of Applied Graphics was transferred from the College of Applied Arts to the College of Fine Arts, together with its teachers and students.

The institute's library of great value was made almost inaccessible and its development was curtailed.

Education had to be reorganised again following the revolution in 1956.

In 1964, another reform came into force. In four years of basic training, students were awarded a diploma giving them the right to teach drawing, figurative geometry and art history at secondary school. The College did not award an art diploma, but in order to provide a higher level of artistic training, the period of study could be extended annually for talented students up to a maximum of three years. In 1971 the College was granted the status of a university. Since 1972, students have been able to spend their summer internships at the college's Tihany Art Camp. Today, students are trained full-time at the Department of Scenic Design.

In the 1960s restorator training was strengthened. The Restorator Department and later the Institute trained restorators in painting, stone sculpture and wood sculpture. Object restorator are trained on a part-time course.

In the 1960s and 1970s the teaching methodology of artistic anatomy, associated with Jenő Barcsay, was completed and has attracted many foreign students ever since. The College's teacher training traditions and its role as a 20th century art academy led to the most recent academic reform between 1988 and 1993. Students can study for a degree in both teacher training and arts at university level for five years. Studio studies in the morning are followed by theoretical and language training in the afternoon. All students can participate in the visual education teacher training programme if they meet the requirements of the aptitude test in the third year, which is organised by the department.

At the end of the last century, the Budapest was home to the institutions of fine arts, thus enabling almost the whole of Hungarian art to take off from Terézváros towards Hungarian and international fame. In addition to the 'enchanted' timelessness of the Epreskert, the Hungarian College of Fine Arts' complex of buildings, the constant presence of art teachers and students carrying their portfoliosand large folders became part of the sight of Andrássy út.

(Katalin Blaskóné Majkó, 2004)

VII. Hungarian art policy and the College of Fine Arts in the 1920s and 1930s

The predecessor of the Hungarian College of Fine Arts in Budapest, the Royal Hungarian School of Fine Arts and Drawing Teacher Training School was founded in 1871 and was renamed the Royal Hungarian College of Fine Arts in 1908. In Hungary, at the end of the last century, it was the only institution providing state-funded art education. It was the only one of the Hungarian Royal Academy of Fine Arts in the year 1896. It was here that future drawing teachers, artists and, until 1896, applied artists were trained.

In 1867, following the compromise agreement governing the constitutional relations between Austria and Hungary, Hungary was granted greater autonomy in the dual monarchy. The country's economic prosperity and industrialisation took off. As a result of the economic boom, the population grew by almost 40% in 30 years. The economic boom led to the modernisation of public education, public health and infrastructure.

József Eötvös, serving as Minister of Religion and Public Education for the second time from 1867 to 71, considered one of his most important tasks, as a follower of the Enlightenment, to reform public education. He considered the promotion of the arts to be an element of state organisation, as he stated in one of his letters: 'Art, apart from the artists who create great things, can only be promoted by promoting individual artists and giving them work'.

In the last third of the last century, the artists' main livelihood was in the construction of national public institutions, and they were commissioned to decorate the exteriors and interiors of buildings. From the 1870s to the 1896 millennium of the Hungarian State, a number of cultural institutions were built thanks to public commissions (the Museum of Fine Arts, the old Art Hall, the Museum of Applied Arts, the Opera House, the School of Applied Arts, the Model School of Drawing). The state administration was aware that if it wanted to put the fine arts at its service, it would have to create the necessary conditions for artists who had not been trained in Hungary to return home, and who had studied abroad - in Vienna, Munich or Paris. State patronage, studios and various grants and tenders were used to attract Hungarian artists living abroad. The Hungarian art scene had previously lacked a national art education institution, and this gap was filled by the establishment of the National School of Art and Drawing.

Efforts to create national art took precedence over all other artistic problems. The direct cultural policy aspects of artistic and educational issues were even more important in the first decades of the century, so it is not surprising that the knowledge acquired in foreign lands could not, in the opinion of many, be the basis of Hungarian art, and therefore did not suit the "guardians" of Hungarian culture. In many cases, however, the attacks were not justified, because in Hungary works of art representing knowledge and taste acquired abroad - no matter how modern and how much they could be classified as part of the trends of European modern art - were sometimes rendered uncompetitive in the Hungarian art scene by a single qualification ("non-national in character"). At the same time, recognising that a close connection with the local landscape and culture was essential to the creation of national art, Simon Hollósy and his colleagues (István Réti, János Thorma), who had already achieved great fame abroad, returned home from Munich and founded the art colony in Nagybánya in 1896. This was not only of epoch-making importance in Hungarian art because it established the new institution of the artists' colony, but also because their work represented a break with the guiding principles of the academy. The free school, which operated within the framework of the Artists' Colony, became a "counter-academy" on a national scale, following the principles of the Julian Academy in Paris. The landscape of Nagybánya provided the perfect setting for plein-air painting. The conservative, academic 'art-hall painters' who regularly exhibited at the Art Hall, were disturbed to see the success of the art colony. Gustáv Kelety, the head of the Art School, outright forbade the students to spend their summer holidays in Nagybánya.

Conflicts between persons and principles (artistic views, teaching methodology) caused problems in the infancy of Hungarian art education. The conflicts made it difficult - but also inspired - the artistic development of the students of the college.

From 1905 on - under the leadership of Pál Szinyei Merse - the artists who opposed the academic approach prevailing at the college and artists following the impressionist principles of Nagybánya also joined the teaching staff, so the balance of power and taste began to change (Károly Ferenczy was appointed professor in 1906, István Réti in 1913 and Oszkár Glatz in 1914).

During the First World War and even afterwards the college was transformed into a military hospital, with teaching taking place in various buildings in the capital, disorganised and without funding. However, in the period following Szinyei's directorship, from 1920 onwards, art education and the reorganisation of the institute were re-launched. The 1920s and 1930s were a remarkable period in the history of the Hungarian College of Fine Arts, marked by conflicts between different schools of thought, artistic trends and teachers. The struggle of opinions can be followed in the journals and art magazines of the time; life of the college was an open and exciting book, although we must remember that the stakes were no less than the reform and transformation of the only Hungarian fine arts institution, so that it would be modern in its organisation and spirit, similar to modern European academies, yet based on Hungarian art.

The college was the arena of official Hungarian art, so the exchanges - not infrequently the press warfare - between artists representing a freer spirit and those advocating more conservative tendencies raised more important issues beyond the battles for teaching positions and personal disagreements. The personality of the teacher and their conception of art, the principles and methods of teaching would determine the future generation of artists, and thus the future of Hungarian art. The new organisational structure of the institution and the reforms in the methods of art education are attributed to Károly Lyka, who was elected rector in 1920. Thanks to the reforms, the educational concept of the college changed, and the rector introduced the principles of the Nagybánya School of Painting: drawing from nature instead of the previous plaster casts, and made participation in summer art camps compulsory. The academic historical painting that had dominated the previous decades began to lose its primacy. At the same time, the introduction of the principles of Impressionist art meant the exclusion of more advanced ideas: post-Impressionist, post-Nagybánya and avant-garde approaches were less appreciated by the school's administration as Lyka did not particularly sympathise with them.

Previously, the college had separated the training of artists and drawing teacher trainees, which led to tensions between the twoo groupss and their professors. They had separate curricula and timetables, teacher trainees received higher scholarships. Károly Lotz and Gyula Benczúr, who taught in the 'artist-training' master schools, did not even set foot in the drawing teacher training departments, while the latter looked down on the artist candidates because they could get in without a school-leaving certificate. This segregation took place under the leadership of Károly Kelety, and was, according to Lyka, brought about by conservative teachers who were concerned about the infiltration of modern ideas into the studios. They wanted to protect drawing teachers from these, as the majority believed that future teachers should remain the guardians of academic art. Lyka merged teaching in the two fields, while at the same time requiring everyone to have a a school leaving certificate. At the same time, the practice of appointing the rector by the Minister of Education and Religious Affairs was changed: the rector's council was now responsible for appointing the rector. Lyka also changed the composition of the teaching staff, inviting progressive artists to teach, who sought to synthesise Hungarian art and modern aspirations. Gyula Rudnay was also admitted to the college during this period. Lyka's modernising reforms and structural changes to the institution, however, also had their opponents. There were those who opposed the unification of art and drawing teacher training, because this also meant a reduction in geometry and other professional hours essential for teacher candidates. The more conservative artists were not happy with the newly appointed teachers, fearing that the newly introduced free choice of teachers would leave them without students and their teaching positions would be jeopardised. Lyka was also attacked, arguing that "... the rector can only be an excellent painter...".

"We need national rather then international art". One of the conservative artists, sculptor György Zala, also called for Lyka's removal by the Minister of Education. Zala, in contrast to Lyka's principles, argued that teaching of art movements should be done away with and the main emphasis should be laid on teaching craftsmanship.

Staff members complained that they had not been consulted with over the appointments of new professors. In response to the attacks on the rector, nearly a hundred students turned up at the minister's office and petitioned in support of Lyka. As a result of the battle of the petitions, the new teachers were allowed to stay. This decision was far from being dependent on the turnout and the reasons given in the petitions. The concept of art policy at the time was that modern art should have some presence in official art.

The new teaching methods of the new teachers during Lyka's rectorship divided the students into several fractions.. One group was made up of Rudnay's students and students of masters close to Rudnay's method, while the other group was made up of students of Vaszary and István Csók, who followed Vaszary’s principles. Gyula Rudnay taught at the college from 1922. After studying in Munich and Nagybánya, he spent several years in Hódmezővásárhely. The uniqueness of Rudnay's works is not to be found in the way they are painted, but in their spirit, their nostalgic mood. Rudnay wanted to create art whose main characteristic is that it is Hungarian. He deliberately chose an old-fashioned, patina-like representation and painting style to represent the national tradition - the Hungarian character - which was the aim of his painting. Rudnay's true greatness lies in his distinctive landscape painting. Recalling the memories of the German Lowlands landscape of the 16th century, 'fresh and young for all its past roots'.

" ... Corrupted by Munich, seduced by Paris, and by the fakeflare-ups, the esprit, the posed theatrical tricks of l'art pour l'art, some Hungarian artists were struck on the forehead, dazzled", he said in a 1929 lecture. At the time of the artistic revolutions and the conquest of the avant-garde, Rudnay's archaic style of representation and his sweetly sultry pictures, combined with his peculiarly Hungarian themes, were a great success at many international exhibitions, although the acclaim was not without critics, such as Ernő Kállai, who described the master's art as "excessively overrated". In his portraits and landscapes, he "wanted to evoke the air of the past of Hungarian history."

János Vaszary studied with Bertalan Székely at the predecessor of the college, the National Institute for the Teaching of Drawing and Design, and then with Ludwig von Löfftz in Munich, but he belonged to the circle of Hollósy. He then continued his studies in Paris at the Julian Academy, which allowed his art to remain French-inspired throughout. The naturalistic traits of his painting were soon replaced by post-impressionism, followed by works reflecting the influence of French Fauvism. He had a significant influence on Hungarian avant-garde efforts. In 1924 he was a founder of the KÚT (New Society of Artists) and in 1925 of the UME (Union of New Artists). The members of KÚT were progressive artists whose aim was to create continuity in modern Hungarian art. The New Artists' Union was a group of young progressive students. Vaszary's presence at the college signified the acceptance of modern European art, but he came under attack as soon as he joined. His detractors saw his overly individualistic art as inconsistent with artist training.

"The first prerequisite for the study of natural forms: the search for and determination of the internal structure, that is, the organic starting point from the inner essential. The forms that appear on the outer surface of objects and shapes are the effects of the inner organic structure." These ideas are analogous to the teaching methods of Klee and Kandinsky. "It is not surprising that this way of thinking seemed alien not only to the rigidly conservative, orthodox academic, but also to the professionals with moderately modern tastes." Vaszary showed his students the albums he had acquired during his trip abroad, and talked about European artists and the principles of modern picture-making. "There is no reason to avoid the movement of progressive great cultures" he wrote in his essay “Modern Art and Nationalism” in 1929. For Vaszary, it was important to adopt the world of colour and form of Hungarian art, but he wanted to synthesise this with knowledge and application of European modern art. Jenő Barcsay, comparing the teaching methods of István Réti - and other teachers - who taught according to the impressionist principles of Nagybánya, and Vaszary, remembers that while studying with Réti specific subjects were to be depicted (e.g. In the latter case, the problems of space and form were the problem after the problems of colour, followed by the problem of movement.

"The fact is that while the students of the other masters had no idea of colour, line, form, space, and what it takes to make a picture, what painting is, we were interested in these things." The critics of the time described him as the most artistic colourist with the finest taste. However, "...with problems such as the nude, he has difficulty, because when he wants to give a sense of construction, he sticks to the surface, nothing behind it." The enthusiastic pupils were not Vaszary epigones however, but developed a completely different individual styles. Vaszary, as well as the more tolerant István Csók, who also studied in Munich and then in France, were teachers with a liberal outlook, who taught according to the Parisian principles and who, because of their different approach, were separated from the rest of the teaching staff. Conservative teachers in the opposite camp, such as Bertalan Karlovszky, said that Vaszary's students were making paintings 'full of stove pipes and rectangles'. After studying in Paris and Munich, Csók settled in Budapest in 1910. The official art policy of the time considered his art 'corrupted' and the recurring theme of his paintings, the nude, to be a libertine subject. The teaching staff was concerned about the influence of the masters on their students. More and more cubist and constructivist works appeared in the classrooms of Vaszary's and Csók's students, and in the 1923 exhibition of sculptures by Vaszary's students at the Ernst Museum, the latter's pupils were also represented. In 1929, at an exhibition in the Art Hall, the students' works were so distinct from those of the others that Elek Petrovics and Tibor Gerevich were 'forced' to pay them an official visit, which was also an excuse to criticise their teaching methods of the above masters.The attacks finally paid off: in 1932, István Csók and János Vaszary were retired on account of their age. But there were several reasons why they were not removed from the cathedra after more than ten years. From 1922 to 1931, until the resignation of Count István Bethlen's government, Count Kunó Klebelsberg was the Minister of Religion and Public Education, who, under international (mainly Italian) influence, supported the new Hungarian artistic endeavours to a certain extent. On the international scene, it was criticised that only and always conservative artists represented the country. His aim was to bring national culture into line with international cultural 'developments'.

Since the college is the spokesperson for the official line, and the free art schools represent a particular line, the minister believed that if the college continued to take a more conservative direction, many talented students would flock to the free schools. That is why he backed Lyka and the new teachers. However, neither Vaszary nor Csók liked the trend most favoured by the minister, the Roman school based on neo-classical principles, a combination of ecclesiastical themes and modern spirit, however modern its adherents thought it to be, and yet the more open aspirations of Klebelsberg's cultural policy offered some security for progressive artists. In addition to the scandals that erupted over the student exhibitions, the change of ministers also contributed to the dismissal of the masters. The new Minister of Culture, Jenő Karafiáth, no longer continued the art policy of his predecessors, nor did he sympathise with Vaszary. There was also a personal conflict between Karafiáth and Csók, as the masters mocked him for one of his strange so-called "fig leaf" decrees. The minister found nude drawing indecent and issued a decree that nude models at the college should use a 'cover'.

János Vaszary and István Csók were joined by artists, critics and supporters. The main argument against their retirement was that they represented the modern spirit at the college and it was feared that in their absence these aspirations would die out completely. However, the retirement of the masters did not mean the retirement of Hungarian art; among their students we could mention Jenő Gadányi, Dezső Korniss, Jenő Medveczky, Sándor Trauner (who later became a set designer), György Kepes, Jenő Barcsay, Gyula Hincz, Tamás Lossonczy, without claiming completeness, who continued the modern artistic aspirations.

Vaszary did not stop teaching. He continued at Klára Rázsó's private school, where he was followed by Lajos Vajda. Vaszary's corrections were followed by Piroska Szántó, who was expelled from the college, Endre Bálint, and Margit Anna, who, although not admitted to the college, cannot be omitted from the roster of Hungarian art.

Eszter Lázár (2015.)